Ever wondered what a medieval saint had to say about immigration chaos?

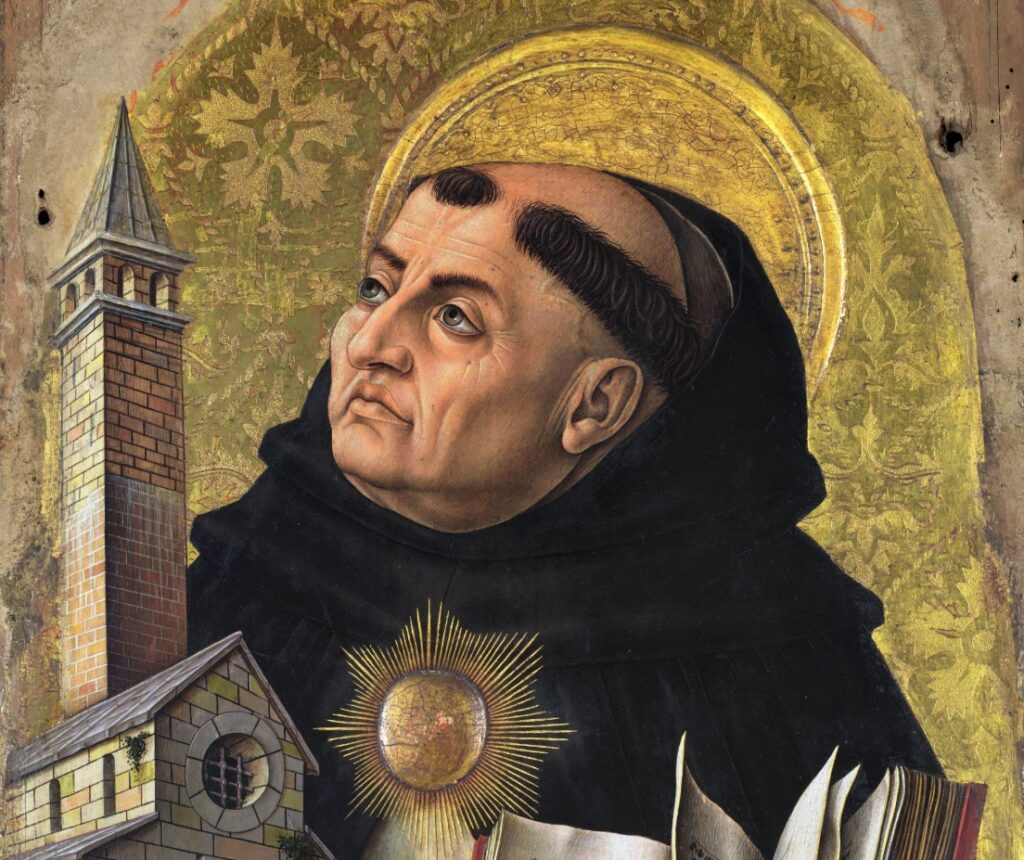

In his book Summa Theologiae, St. Thomas Aquinas gave a kind but practical view on immigration that influenced the West for nearly 1,000 years.

“Man’s relations with foreigners are twofold, peaceful and hostile, and in directing both kinds of relation the Law contained suitable precepts.”

1. Keep it proportional! Immigration must be measured so newcomers can truly integrate into the nation’s culture and faith. No overwhelming floods!

2. Citizenship? Earn it over time. Full rights only after THREE generations—to safeguard the country’s traditions, religion, and laws. Patience pays off!

3. Citizens first, always. The state’s number 1 job is protecting its own people’s well-being. Helping outsiders? Sure, but NEVER at your citizens’ expense.

But here’s the tough truth: Aquinas warns that some peoples or nations are just incompatible – treat them as “foes in perpetuity” to preserve peace.

In Thomistic philosophy, the order of charity is a divine hierarchy: love God above all, then oneself rightly, followed by those closest by duty and proximity; family, neighbors, and fellow citizens before extending to all humanity. This structure ensures universal charity without neglecting specific obligations, as encapsulated in “charity begins at home.”

A father’s primary duty is to his immediate family, secondary to extended kin and neighbors, and tertiary to the wider community. Charity includes welcoming strangers in urgent need, but aid must be proportionate to one’s means and priorities, avoiding neglect of those entrusted to us.

This balances against two extremes: indifference to outsiders or excessive generosity that harms one’s own.

Aquinas viewed political community as friendship under just laws, with peace as the “tranquility of order.” Admitting strangers should enhance civic virtue without straining bonds; large-scale influxes risk altering culture, language, and religion. True assimilation requires newcomers to uphold the nation’s values, laws, and common good, while the nation extends charitable integration without exploitation.

In the Summa Theologiae, Thomas Aquinas articulated a framework on the reception of foreigners that is at once humane and prudential. One that influenced Western political thought for centuries.

First, the admission of newcomers must be measured and proportionate, so that genuine integration into the polity’s culture, laws, and religious life is realistically achievable rather than merely aspirational.

Second, full civic membership, together with its attendant political rights ought not to be immediate. Aquinas suggests a gradual incorporation across generations, safeguarding the stability of the constitutional order and the continuity of the community’s moral and religious foundations.

Third, the bonum commune, the common good of existing citizens remains the supreme responsibility of the state. Charity toward outsiders is virtuous, but it cannot override the primary duty a political community owes to its own members.

Yet Aquinas closes with a sober caution: history shows that certain political communities may be fundamentally irreconcilable in their principles or allegiances. In such cases, he warns that enduring enmity may be an unavoidable reality in the conduct of states.

Aquinas rejects borderless indifference or absolute barriers, affirming national sovereignty alongside universal Christian hospitality, within reason. In cases of unjust aggression, just war is a moral duty to defend peace and justice, guided by right intention and proportionality.

Patriotism means caring first for your own community, while still being willing to help others. Immigration can be a good thing, but it depends on whether it supports peace, good values, and the common good. Newcomers should be integrated in a balanced way so that society as a whole can grow and thrive.